Sex & the City. Fra autodeterminazione di genere e governo della città

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.13133/2532-6562/17369Keywords:

gender urban planning, gender mainstreaming, sexed cityAbstract

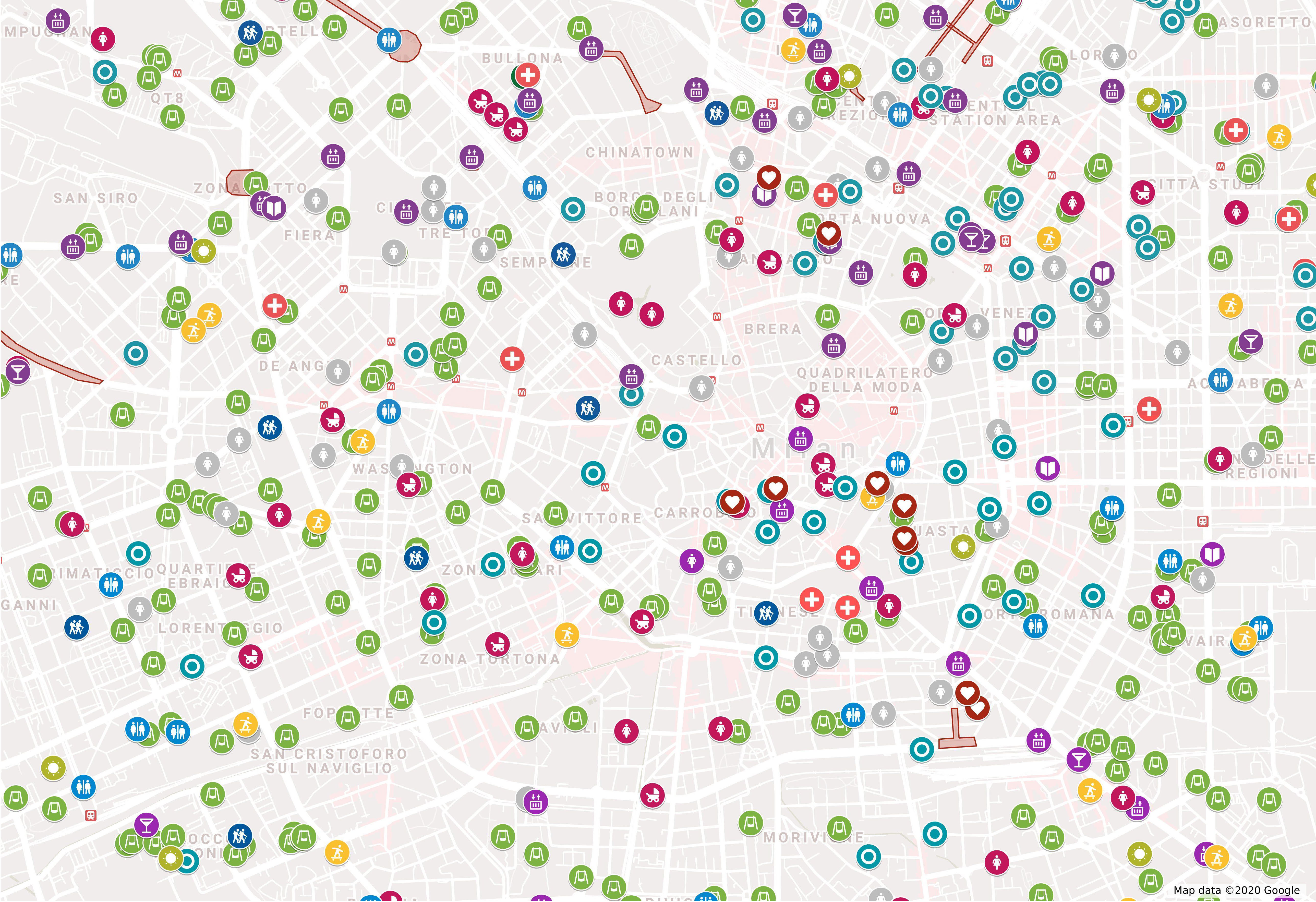

What is the “gender” of the cities we live in? Who are the streets, parks, squares, statues, monuments, subway stops, public buildings named after? What kind of message does the symbolic sphere of the city convey through these choices? And also: what services does the city offer to support women's lives? Are public toilets, nursery schools and anti-violence facilities sufficient to cover the needs of a society that aspires to real equality between genders? What role do grassroots initiatives play today and what role can they play in shaping the inclusive city of tomorrow? Our contribution is rooted in the framework of the Sex & the City research, commissioned in January 2020 by Milano Urban Center, a think tank on urban transformations promoted by the Municipality of Milan with Triennale Milano. The aim of the research is to observe how the cornerstones of gender discourse – which concern the relationship between production and reproduction, policies on women’s bodies, gender violence, the right to the city – translate into space and politics. The heart of the research is a Gender Atlas of Milan: a critical mapping in which concepts become physical spaces that translate specific needs, and networks of subjects that animate and give meaning to the existence of those spaces. The thesis that we intend to support here, starting with some gender claims in the city of Milan, is that these represent – as a direct manifestation of a need for at least a part of the citizenry – the basis on which to graft public policies that are more attentive to the needs of women and gender minorities, capable of translating into long-term changes. The horizon is an idea of inclusive and welcoming planning, in which public space is the place where the multiple voices that make up the community emerge and coexist, and the city a place where differences are recognized and valued.

Che “genere” di città abitiamo? A chi sono intitolate, le vie, i parchi, le piazze, le statue, i monumenti, le fermate della metropolitana, gli edifici pubblici? La sfera simbolica della città che tipo di messaggio veicola attraverso queste scelte? E inoltre: che servizi offre la città a supporto della vita delle donne? I servizi igienici pubblici, gli asili nido, i presidi per il contrasto alla violenza sono sufficienti a coprire le esigenze di una società che aspira alla reale parità fra i generi? Che ruolo hanno oggi e che ruolo possono avere le iniziative dal basso nel dare forma alla città inclusiva di domani? Il nostro contributo si radica nella cornice della ricerca Sex & the City, commissionata nel gennaio 2020 da Milano Urban Center, un think tank sulle trasformazioni urbane promosso dal Comune di Milano con Triennale Milano. L’obiettivo della ricerca è osservare è come i capisaldi del discorso di genere – che riguardano il rapporto fra la produzione e la riproduzione, le politiche sul corpo delle donne, la violenza di genere, il diritto alla città – si traducano in spazio e politiche. Il cuore della ricerca è un “Atlante di Genere di Milano”: una mappatura critica in cui i concetti diventano spazi fisici che traducono esigenze specifiche, e reti di soggetti che animano e danno senso all’esistenza di quegli spazi. La tesi che in questa sede intendiamo sostenere, a partire da alcune prese di parola di genere nella città di Milano, è che queste rappresentino – in quanto manifestazione di un bisogno di una parte della cittadinanza scevra di intermediazioni – la base su cui innestare politiche pubbliche più attente alle esigenze delle donne e delle minoranze di genere, capaci di tradursi in cambiamenti di lungo periodo. L’orizzonte è un’idea di una pianificazione inclusiva e accogliente, in cui lo spazio pubblico sia il luogo in cui emergono e coesistono le molteplici voci che compongono la collettività, e la città un luogo in cui le differenze siano riconosciute e valorizzate.

References

Alderman D., Inwood J. (2017). «Street naming and the politics of belonging: spatial injustices in the toponymic commemoration of Martin Luther King, Jr.». In: Rose-Redwood R., Alderman D., Azaryahu M. (a cura di). The Political Life of Urban Streetscapes: Naming, Politics, and Place. Abingdon, U.K.: Routledge, 259-273.

Aristotele. (1973). Opere, vol. IX, Bari: Laterza, 9-14.

Aureli P.V., Shéhérazade M.G. (2020). «Orrore Familiare. Per Una Critica Dello Spazio Domestico». In: a Florencia Andreola (a cura di). Disagiotopia. Malessere, Precarietà Ed Esclusione Nel Tardo Capitalismo, Roma: DEditore.

Beebeejaun Y. (2017). «Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life». Journal of Urban Affairs, 39 (3). Taylor and Francis Ltd.: 323–334. doi:10.1080/07352166.2016.1255526.

Boccia T. (2016). «Habitat III: Theories and practices of the women facing the global challenges in cities». TRIA Territory of Research on Settlements and Environment 9 (1): 17-20.

Criado Perez C. (2020). Invisibili. Come Il Nostro Mondo Ignora Le Donne in Ogni Campo. Dati Alla Mano. Torino: Einaudi.

Darke J. (1996). «The Man-Shaped City». In: Booth C., Darke J., Yeandle S. (a cura di). Changing Places: Women’s Lives in the City, London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd, 88–99.

Gnatiuk, O., Glybovets, V. 2020. «‘Herstory’ in History: A Place of Women in Ukrainian Urban Toponymy». Folia Geographica, 62(2): 48-70.

Gutiérrez Mozo M.E. (2011). «Introducción a La Arquitectura y El Urbanismo Con Perspectiva de Género». In: Gutiérrez Mozo M.E. (a cura di). La Arquitectura y El Urbanismo Con Perspectiva de Género. San Vicente del Raspeig: Centro de Estudios sobre la Mujer de la Universidad de Alicante, 9–22.

ISTAT. 2020d. L’allerta Internazionale e Le Evidenze Nazionali Attraverso i Dati Del 1522 e Delle Forze Di Polizia. La Violenza Di Genere Al Tempo Del Coronavirus: Marzo – Maggio 2020. Roma.

Kern L. (2020). Feminist City. Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. Londra; New York: Verso Books.

Pérez Prieto L. (2016). «Women’s right to the city. A feminist review of urban spaces». TRIA Territory of Research on Settlements and Environment, 9 (1): 53-66.

Sánchez de Madariaga I. «Mobility of Care: Introducing New Concepts in Urban Transport». In: M. Roberts e I. Sánchez de Madariaga (a cura di) (2013). Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

Seager J. (2020). L’atlante Delle Donne. Torino: AddEditore.

Valentine G. (1989). «The Geography of Women’s Fear». Area 21(4): 385–390.

Yeandle S. (1996). «Women, Feminisms and Methods». In: Booth C., Darke J., Yeandle S (a cura di) Changing Places: Women’s Lives in the City, London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd, 2–15.

World Bank. (2017). Global Mobility Report https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/28542/120500.pdf?sequence=6

Zanuso L. (2016). «Le milanesi al lavoro». In: Cicciomessere R., Zanuso L., Ponzellini A.M., Marsala A. (2016). A Milano il lavoro è donna. Il mercato del lavoro milanese in un’ottica di genere. Italia Lavoro S.p.A (a cura di). Milano: EQuIPE 2020.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Azzurra Muzzonigro, Florencia Andreola

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

NOTA DI COPYRIGHT

Proposta di licenza Creative Commons

1. Proposta per riviste Open Access

Gli autori che pubblicano su questa rivista accettano le seguenti condizioni:

Gli autori mantengono i diritti sulla loro opera e cedono alla rivista il diritto di prima pubblicazione dell'opera, contemporaneamente licenziata sotto una Licenza Creative Commons - Attribuzione che permette ad altri di condividere l'opera indicando la paternità intellettuale e la prima pubblicazione su questa rivista.

Gli autori possono aderire ad altri accordi di licenza non esclusiva per la distribuzione della versione dell'opera pubblicata (es. depositarla in un archivio istituzionale o pubblicarla in una monografia), a patto di indicare che la prima pubblicazione è avvenuta su questa rivista.

Gli autori possono diffondere la loro opera online (es. in repository istituzionali o nel loro sito web) prima e durante il processo di submission, poiché può portare a scambi produttivi e aumentare le citazioni dell'opera pubblicata (Vedi The Effect of Open Access).